the taste hierarchies of letterboxd

✰ not all inspiration is created equal : an ode to the alleged unconventional ✰

Citizen Kane. (1941). Directed by Orson Welles. RKO Pictures.

When I first heard the name Citizen Kane, it was spoken like scripture. It was the film, the one that defined an art form. Before I even set foot in film school, countless video essays, articles, and reverent whispers had built its legend in my mind. It loomed large, casting shadows over all the films I had loved growing up. It was a masterpiece, they said. Essential viewing. When the moment finally came, the reality couldn't have been further from the legend.

I hated it. I found it painfully boring. It wasn’t the transformative experience I had been promised; it felt like a chore. And the worst part? I couldn’t admit it. Not out loud. In the world of filmmakers and critics, to not revere Citizen Kane is practically heresy. I wrestled with my own discomfort. Could it be that I was missing something?

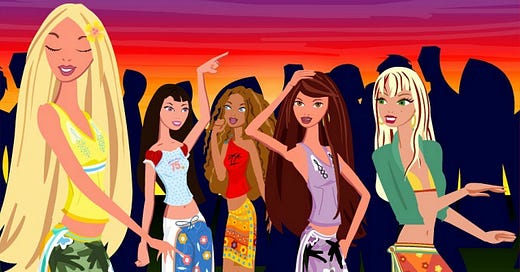

So I stayed quiet. I wondered if I was a fraud for wanting to make films but not feeling moved by this cornerstone of cinema? It pressed against me every time someone asked for my “serious” film recommendations, every time I saw a peer log a Palme d’Or winner on Letterboxd while I was rewatching MyScene: Jammin’ in Jamaica ( I will defend Madison to my last breath.). It was a quiet, persistent reminder that I didn’t quite fit the mold. So through that my burner Letterboxd account was born.

My Scene: Jammin' in Jamaica. (2004). Directed by Ethan Fogel. Mattel, Inc.

It became apparent to me that there was an unspoken hierarchy in film — a sense that some inspiration was better than others. Certain films, directors, and aesthetics were deemed “highbrow,” while others were dismissed as frivolous or amateur.

In film school, this hierarchy was unavoidable. It seeped into conversations, critiques, and casual jokes. You could feel the pressure to conform to it, to model your taste after the greats. But the thing is, I’m sure Orson Welles doesn’t care that I didn’t personally enjoy his film. And you shouldn’t either.

Taste is political. It’s shaped by privilege, by access, by tradition. In the film world, the tastemakers are often critics, programmers, and academics—people with the authority to decide what’s worthy of recognition. And even though this is shifting particularly as our tastemakers diversify, at one point in time these tastes aligned with a particular aesthetic: the serious, the male, the cerebral, the white, the “important.” This not only narrows creative possibilities but also marginalises alternative storytelling traditions.

I’m aware I’ve not discovered taste hierarchy the way in which the first humans discovered fire, but its impact weighs heavy. Taste hierarchies in Western culture elevate certain forms of inspiration—classics, prestige films, and works by “great masters”—to the exclusion of others. This creates a narrow framework for what is considered “valid” inspiration and excludes diverse, equally valuable sources of creativity. This not only narrows creative possibilities but also marginalises alternative storytelling traditions.

Take, for example, filmmakers who don’t pull from an extensive Western film library. If a director is more inspired by a childhood spent watching telenovelas or by the colour palettes in shoujo anime than by the films of Kubrick or Fellini, their story is not less worthy of being told. Yet, taste hierarchies perpetuate the myth that knowledge of a Western traditional canon is an absolute must for artistic legitimacy. This myth disregards how creativity thrives on personal, visceral connections to art, no matter its origin.

Hunter x Hunter. (2011). Directed by Yoshihiro Togashi. Madhouse.

This exclusionary framework often overlooks non-Western and popular forms of storytelling, which are equally capable of evoking profound emotion and sparking imagination. Bollywood musicals, African oral traditions, or Indigenous Australian dreamtime stories provide different lenses to understand the world, yet they’re often dismissed as less sophisticated by institutions steeped in Western taste hierarchies. In this way, taste hierarchy isn’t merely a personal preference; it’s a gatekeeping tool that implicitly defines whose stories are seen as valuable. I’m aware there is a rising global influence of non-Western filmmakers and films—such as the international acclaim of Parasite or the growing appreciation for Nollywood. That means the boundaries of these taste hierarchies are beginning to shift but these creators remain underrepresented within the broader industry and institutional frameworks so there is still work to be done.

This argument isn’t about dismissing the canon but about decentralising it. The greats have value, but so does the spark of originality found in allegedly unorthodox inspirations. By embracing a broader, more inclusive understanding of what constitutes valid artistic references, we create space for voices that might otherwise be drowned out by the echoes of tradition.

But what happens when your taste doesn’t align with this tradition? What if your favourite films are the ones that don’t impress the Letterboxd bros, the ones that don’t show up on “greatest of all time” lists? Does that make them less valid? In my opinion the answer is no. Your favourite films don’t have to entertain, impact, or resonate with anyone but you. They are yours, and that makes them enough.

If you look at “low-brow” rom-coms, like The Kissing Booth or Set It Up, they may not aim for artistic brilliance, but for many, these films are easy to enjoy—fun to laugh at, even if they don’t resonate deeply. You don’t have to put down your “high-brow” cinema to appreciate them, but it’s worth being open to the fact that some people genuinely love them. And if you find yourself thinking, “What they did there is actually kind of cool,” that’s great too—it all adds to your creative perspective.

What matters is that you learn what you love and why you love it. That you master the art of telling the story that only you can tell, without worrying whether it meets some arbitrary standard of sophistication. For me, the most powerful inspiration has always come from what feels real to me, what moves me on a gut level. It’s not about what’s “objectively” good; it’s about what resonates.

The beauty of art is that it’s deeply personal. It comes from your voice, your experiences, your perspective. No one else sees the world the way you do, and that’s your power. But it’s easy to suppress that power, to let the pressure to conform drown out your individuality. We tell ourselves stories about the kind of artist we should be, about the kind of work we’re supposed to make. And in doing so, we lose sight of the stories that are dying to come out of us. What would happen if we let go of those stories? If we stopped chasing external validation and started creating for ourselves?

Some filmmakers jump to overly replicate successful formulas or revered styles, and as a curator it is always so refreshing to see someone who breaks free from cycles of mimicry, find a fresh approach and within that you can hear their distinct voice. Embracing this mindset opens the door to a richer creative landscape, where seemingly opposing influences coexist.

Kill Bill: Vol. 1. (2003). Directed by Quentin Tarantino. A Band Apart; Miramax Films.

If the likes of Scorsese or Tarantino genuinely light your creative fire, embrace that. But don’t stop there—explore why their work resonates with you, and use that as a starting point to tell your own story. The issue isn’t about who inspires you but about making sure your work reflects your voice, not theirs. When you pull from what inspires you most, ask yourself: What am I drawn to? What do I want to say with this? The act of creating should feel like adding your own fingerprint to the larger conversation.

Multiple things can exist on the same plane of influence. Your creative DNA is richer when it weaves together everything you love, no matter where it comes from. When you allow different types of media and experiences to share equal footing in your creative process, you stop judging yourself for your preferences. It no longer matters if your favourite film of the year was a critically panned blockbuster or if you cry every time you watch The Parent Trap. By giving yourself permission to draw from whatever moves you, you create a freer, more authentic space to work in.

The Parent Trap. (1998). Directed by Nancy Meyers. Walt Disney Pictures.

Who says a B*Witched music video can’t be as inspirational as a Bergman film? Both can spark ideas, evoke emotions, or challenge you to think differently about your craft. One might influence your colour palette or pacing, while the other might inspire a narrative or tone. Together, they enrich your work in unexpected ways.

Often, it’s the contrast between influences that can create the most striking work. Imagine blending the epic scope and drama of City of God with the humour of Shrek 2, or using a heartfelt coming-of-age anime like Ore Monogatari!! as a reference for a social realist short film. These seemingly disparate elements can collide to create something entirely fresh.

Shrek 2. (2004). Directed by Andrew Adamson, Vicky Jenson, & Kelly Asbury. DreamWorks Animation.

City of God. (2002). Directed by Fernando Meirelles & Kátia Lund. O2 Filmes.

Allowing yourself to be influenced by a wide range of sources doesn’t dilute your creativity—it enriches it. You’re no longer confined to the boundaries of what is deemed “prestigious” or “appropriate.” Instead, you’re drawing from a broader palette, one that reflects the full spectrum of who you are, what you’ve experienced, and what excites you.

Ryan Coogler on the record has cited Puss in Boots: The Last Wish as a major influence on Sinners. He specifically referenced the villain Death from the animated film with his piercing red eyes and chilling demeanour. This was a template for crafting Remmick, the vampire antagonist in Sinners

Sinners. (2025). Directed by Ryan Coogler. Proximity Media. / Puss in Boots: The Last Wish. (2022). Directed by Joel Crawford. DreamWorks Animation.

Art is not a competition. It’s not about measuring up to someone else’s idea of greatness; it’s about daring to tell your story, your way. The films, songs, and shows that stir something in you; whether they’re universally acclaimed or wonderfully obscure. The art that shape your creative voice. Not every film on My Letterboxd Top 4 will grace a “greatest of all time” list, but they remind me of what storytelling is at its core: a reflection of who we are, with all our contradictions and passions. So, make the films, write the stories, and create the art that feels like home to you because there is power in authenticity.

Please find below my current Letterboxd Top 4

13 Going on 30

Lady Bird

Rodger and Hammerstein’s Cinderella

Touki Bouki

with love,

Aisha ✰

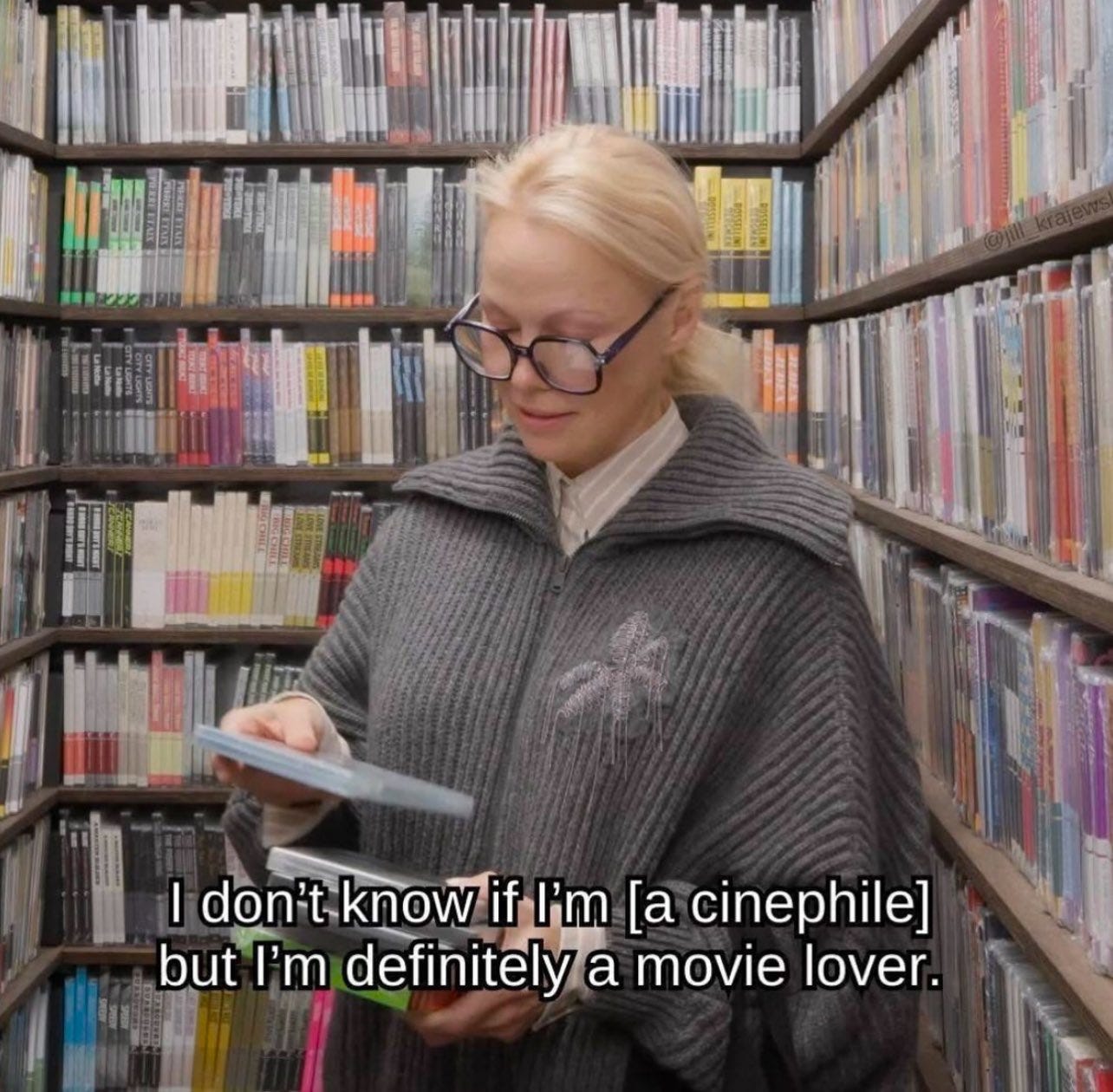

Loved this essay! As an aspiring cinephile, I, too, sometimes feel pressure to watch and deconstruct certain films that are deemed as "high brow", but some of these critically acclaimed movies might be moving for some, but can be deeply boring and uninspired, in my opinion. Taste is subjective, and like you suggest in your piece, most of these holy grail films were given the title by privileged white men who only see the world from their perspectives without acknowledging the nuance and realities that other cultures face on the daily. At the end of the day, movies are just about the experience you have when watching! It's different for everyone.